|

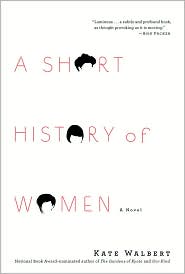

A Short History of Women by Kate Walbert Published by Simon & Schuster 256 pages, 2009

|

Suffragette City Reviewed by Diane Leach Dorothy Trevor Townsend is starving herself to death. Her cause is not anorexia, but suffrage. The year is 1914, and though a war is on, the brilliant Townsend is doing her best to make a statement, to be heard of above the horrible din of war. She is willing to die for her cause, heedless of her children, Evelyn and Thomas, of her lover, William Crawford, of her mother, who will be stuck with her orphaned children. Dorothy dies for her cause, and is immortalized on a commerative postage stamp, a burden or honorific to be borne by her descendants. Author Kate Walbert has created an interleaved narrative of five generations of Townsend women, moving across time from England to San Francisco to New York City. In each era another Townsend finds herself fighting for her place among men: Evelyn, who emigrates to New York, penniless, to become a great scientist, her niece, Dorothy Townsend Barrett, a woman who marries war hero Charles and does all the right things until, at age 75, she can no longer tolerate conformity’s cage, her daughters, Caroline and Liz, one a money manager, the other a frantic potter/mother of three, and their daughters, who are yet too young to do much but rebel, college style: Caroline’s daughter, Dorothy, insists her mother call her Dora, after martyred Dora Maar. Walbert moves between present and past, shifting viewpoints along with historical trappings. The past rubs against the present, never quite joining: when Dorothy Townsend, daughter of Thomas, attempts to contact her Aunt Evelyn at Columbia University, Evelyn refuses to respond. We are never sure why. Nor are we given any sense of closure: a woman’s life is one of struggle against men, regardless of era. Certainly sexual inequity is alive and well, but it is difficult to take that as a horrible affront in light of current matters. That is, yes, it is horrible to be female in certain parts of the world. No question, no argument. But it is not horrible to be Caroline Townsend, frantically checking her mother’s blog, where Dorothy is typing a weird little screed honoring Florence Nightingale. Nor is it horrible to be Liz Barrett, with her television producer husband, in-vitro twins, and permanent nanny. Is Liz Barrett’s life hell? Sure. But it is a self-created hell, one that can only exist in a wash of privilege and cash. Does Liz loathe taking her daughter on play dates? Sure. But most of us don’t have five seconds for such silliness. It is here that I choked: Walbert is a good writer. She is the recipient of numerous prestigious awards; part of A Short History was excerpted in The New Yorker. But her essential premise is drowned out just now by tent cities and failing banks and an unwinnable war. It’s difficult to work up sympathy for a woman who will starve for a cause rather than care for her children, and it’s hard to understand why her granddaughter will, in old age, abruptly decide to throw over her life -- and her befuddled-if-loving husband of over 50 years -- to blog about Florence Nightingale. As for Caroline and Liz, well, Liz has five hours a day to throw pots. What female out there wouldn’t sell her soul for five hours daily to do creative work? Liz feels lonely and unfulfilled? Join the party. For all this, Walbert does best with Townsends operating in the modern day. Evelyn, who arrives in New York during World War II, makes the acquaintance of Stephen Pope, an older man who takes her in. The two live together until Pope’s death, which we are told in 1985 was “many years ago.” The circumstances of their relationship are never made clear, though we wish they were. A 1973 featuring consciousness-raising scene featuring Dorothy Townsend Barrett (the Dorothy who later blogs) is searing: the hostess, while hollering incessantly for Sissie, the Black maid, confesses her husband is homosexual. The other women, drinking gin, admit to premarital abortions, before guiltily inviting Sissie to join them. And Walbert’s evocation of Caroline, the lonely divorcee, Googling her ex late at night while longing for young Dora Maar, are both dead-on and deadly: none of Caroline’s fiercely won wealth will not assuage her loneliness. Ditto Liz, drunkenly reading another mother’s “anxiety journal” while on the aforementioned playdate. Walbert’s complex sentences and meticulous detail could serve novice writers in showing rather than telling. There is Evelyn’s D-Day New York, a jubilant city crowded by celebrants dancing in the streets, a sharp contrast to Liz’s post 9/11 New York, where psychologists attempt to reassure jittery parents that their children are safe, that keeping an “anxiety journal,” will lessen their impossible burden: the inescapable weight, no matter the era, of marriage and motherhood. | June 2009

Diane Leach lives in northern California with her husband and cat. When not reading or writing, she regularly burns herself in the kitchen. |